Pulling for Latoya – Jackie Shea

- No Comments

This was my infusion week. My drip line was removed yesterday, and I am restlessly recovering now. During infusion weeks, I have a hard time deciding what to write/when to write/how to write. It seems like all of my energy— creative and otherwise— is sucked from me and stuffed in a bag for safe-keeping until I’m ready to play again. How do I rally? Day one of my infusion, I watched that Tony Robbin’s documentary everyone is raving about, “I Am Not Your Guru.” It’s a good watch — “I mean nothing mind-blowing, nothing I don’t already know,” says my self-righteous ego.HAHAHA. Except that I did learn something new and my mind was blown over this one thing: Push motivation vs, Pull motivation. Push motivation is exhausting, he says, you’re pushing yourself, using willpower and discipline to accomplish your goals. The push will never last long-term because you get burnt-out. PULL motivation, on the other hand, requires no “rallying,” no forced effort; you are being pulled—you want to do it, you don’t have to do it. This is crucial advice for those of us who are sick—so sick that there’s no room for push. So sick that push can actually delay healing and drain our adrenal glands. PULL, however, feels fulfilling, joyful and bring us toward healing. So, I thought, what am I pulled to write about this week while my IVIG infusion drips? There’s something I haven’t been able to stop thinking about for a couple of months now—something I feel utterly PULLED towards, therefore, something easier to write about with an IV in my arm, aching pain circulating through each cell of my body, and a deep exhaustion that makes me wonder if I’ll ever stand up again. I am pulled to an upright position. I am pulled to an upright position for Latoya and all of those just like her.

In early June, I sat in static LA traffic, the sun blasting through my windows— attempting to blind me or burn me, adding pressure to an already tense situation. I sat, nail- biting, 1.5 miles from my home (a ride that should take 3 minutes), watching the red light change to green, to yellow, to red again. . .on repeat. I switched on KPCC, our local NPR, and happened to catch A Martinez interviewing John Hwang, creator of “Skidrow Stories,” an online photography series documenting the lives of the homeless that live on skid row in Downtown LA. My mind was ripped from self-obsession, traffic obsession, obsession around my illness, and directed toward the immense calamity happening just 7 miles SouthEast of where I luxuriously sat. I was PULLED, pulled to know more, pulled to help, pulled especially in the direction of one woman he met on skid row. I wrote to John after I heard the interview asking if I could write about him, his mission, and his friend, Latoya—he graciously agreed and thanked me for my interest. I also asked if I could accompany him one time which he kindly agreed to as well. I love the work John Hwang does—the work he was pulled to do.

Standing on a bridge in downtown LA, killing time in order to wait-out the traffic (yes,traffic, the way I was introduced to him. . .maybe there are benefits to traffic), John randomly chatted with another pedestrian on the bridge—nothing out of the ordinary, just some face-to-face human connection—something that, I suppose, IS becoming extraordinary. John remembers, “So we’re just having this conversation and then he tells me he was on the bridge because right before he saw me he was going to jump off and kill himself…He said that somehow our conversation made him feel better and gave him hope in life…” That moment inspired John to spend time on Skid Row—just…talking to people. In an effort to share these stories—of tragedy AND triumph— with his friends, he pulled out his camera and asked if he could take someone’s picture. Hwang has no interest in exploitation, he has never had a gallery or exhibit—he even turned down CNN’s interest in making a documentary series. But the pictures are what put John Hwang, “Skid Row stories,” and it’s inhabitants in the spotlight. It’s what helped us to see the people, and hear their voices…#LIVESMATTER. Skidrow Stories is a way to support and encourage the thousands who live forgotten and ignored. John Hwang is actively changing the lives of people on Skid Row by listening to them. By listening to people like Latoya…

Latoya is a woman who would likely intimidate me on the streets: angry and quietly volatile— that’s how I imagine her. Like most people who present themselves with anger, drug addiction or mental illness, there is a story, a background. A story that needs to be heard and loved, not overlooked. Latoya has been hardened from unfathomable trauma, a life so unfair it seems like fiction. John noticed that every time a dog would pass her by, she’d soften, and her tender heart— her innocence—would break through like a bit of light at the end of a long storm. Hwang questioned her one day on why she had such a different reaction to dogs. She said, “dogs would never hurt you like people do…”

Latoya was repeatedly raped by her stepfather until she was 11 years old when she decided to run away. Her family chose not to look for her so they could continue collecting welfare checks on her behalf. She met a pimp on the streets as a pre-adolescent. When Latoya was 11, she was in the throes of human-trafficking and working as a child prostitute. When she contracted HIV in her late teens, she was left— dropped and abandoned…again. That is when she started using hard drugs on the streets. Latoya prefers to stay on drugs in an effort to numb her sense of worthlessness and loneliness. How many people only see “homeless drug-addict,” when they look at her? I wonder. Her story is, unfortunately, not even close to “unheard of.” Her story is one of tens of thousands.

When I was young and naive enough to think that the world could operate in “fair terms,” I thought a lot about the homeless community. I remember driving by a vacant, off-white house, the paint was peeling, the windows were boarded up, and the front door seemed to be made of steel. It was a big-enough house—big enough to make me wonder why it was taking up all of that hardened space, dead energy, offering nothing back to the world. People were living on the streets, and so I wondered like I thought anyone would, “why don’t we fix that house up for the homeless.” I would see this could-be-shelter from the back seat of our suburban SUV and have grand fantasies of cleaning up the place, and painting it some bright color, inviting all of the homeless people nearby to live inside. I imagined myself cooking for them (I owned one of those cookbooks for kids so I could get by). I imagined smiling and laughter: a community of strangers feeling loved, seen, and heard. I felt pulled to make that happen and didn’t know where to begin (because I was like eight). As time passed and my innocence passed with it—I came to realize the vastness of the homeless community, the intricacies of our government, and then I was really stumped. I turned a blind eye.

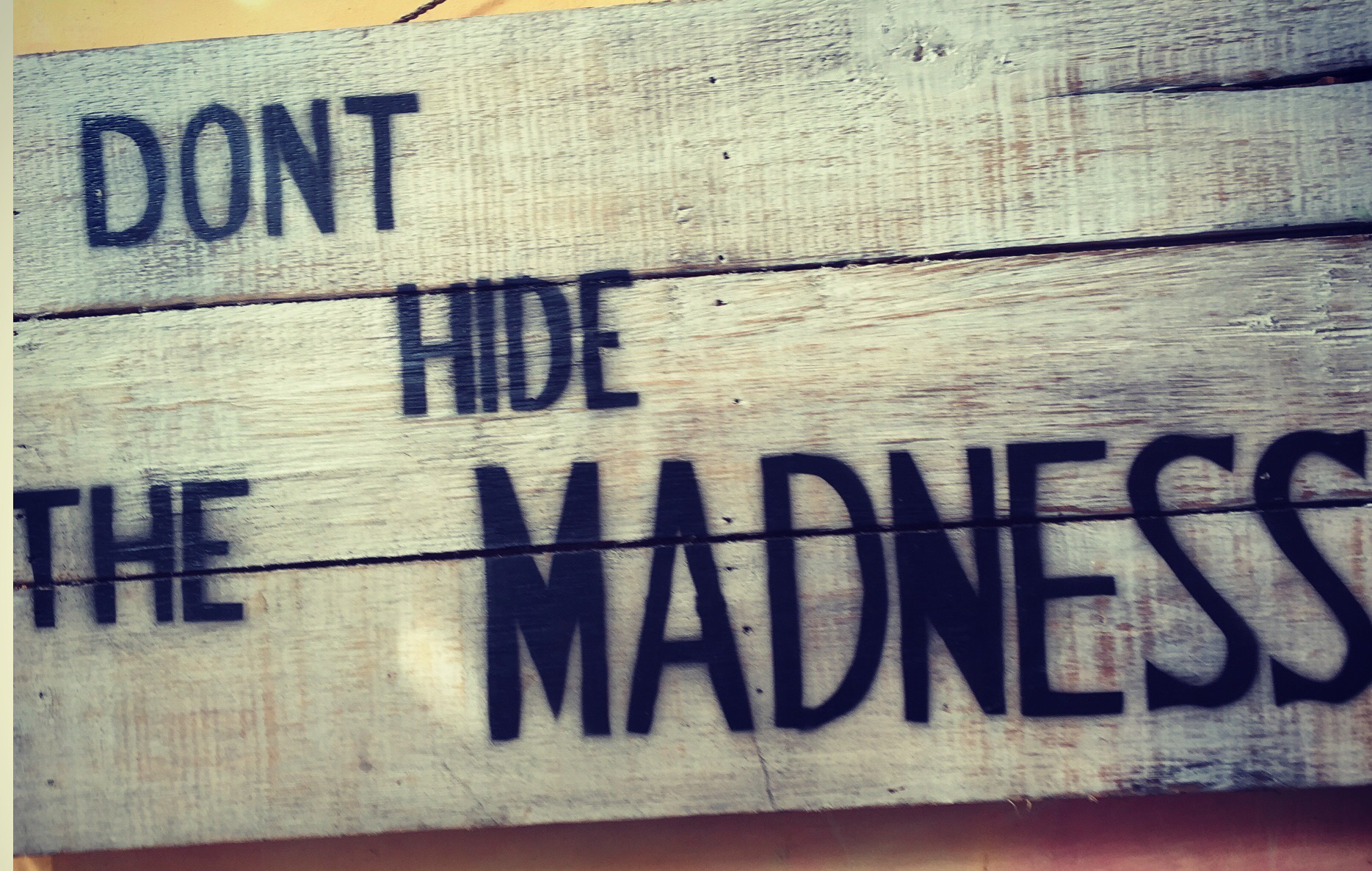

I live in Los Angeles, a city where homelessness is multiplying daily right alongside the billionaires. I drive past people all day, every day. Women and men walk the double yellow line with signs like, “please have compassion. anything would help.” They stare at me, and I usually have nothing to give—sometimes a Lara bar or two, but more often than not, I just look away. In fact, I usually lock my door because I’ve been taught (through experience) that as a small woman, I am unsafe. But this epidemic cannot be denied. All people deserve to be seen and heard. I feel pulled to do something. I want to know Latoya. I want to know all of the pre-adolescent girls, gearing up to run away from home because they are being raped by their guardian, and I want to take them to my magical bright house where we smile and make food all day. I felt inspired to get immediately over to Skid Row and talk to people, too. Maybe even find her, hug her, love her. And I feel completely unsafe doing that on my own, but I can’t ignore the PULL I feel, the aliveness that pull generates.

Yesterday, I got shit news. I received scary blood test results that sent my central nervous system into an anxiety-ridden shock and eventual collapse. Just as I was pulling myself together from that news, I got the news that I was denied federal disability because my condition isn’t “severe enough,” and I can “adjust to different work even though I am hindered.” And then I cried. I cried because I feel abandoned by the system, by my doctors, by the minimal friends and family who haven’t shown up, and by my body. When I think about my childhood, I don’t just have abandonment issues because of my parents. I think about all of the onlookers—the neighbors who didn’t call the cops, the family members that didn’t rescue me, the teachers that never checked in when I was clearly losing my shit, the cops that didn’t show up, and the justice system for letting down my mother and therefore me. It’s those people that I WISH would have said something. . . at least acknowledged what was happening and asked if they could help. I felt all of that sadness again yesterday, the heartbreak. And with my own devastation, I felt an even stronger pull to tell Latoya’s story—because none of us should be denied our truth.

With love,

Jackie

PS: find skid row stories on Facebook